Information

Perse the Zombie Demon

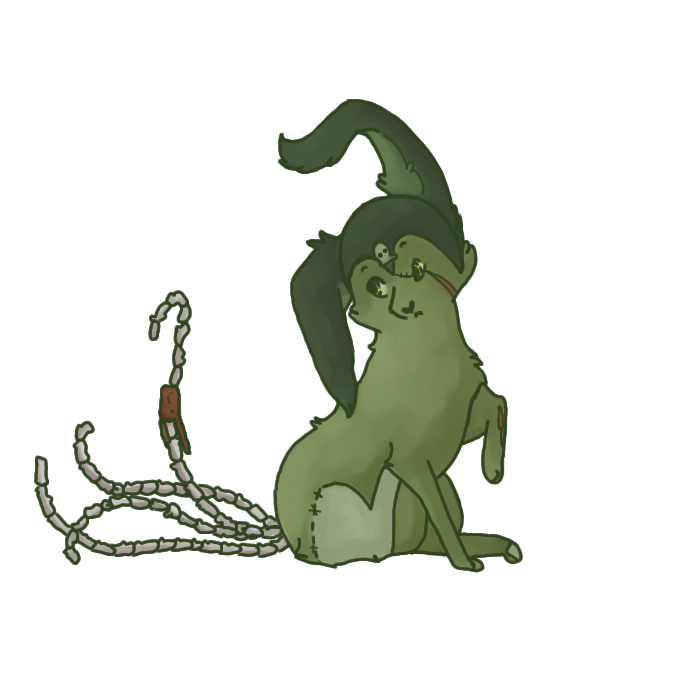

Noveen

Legacy Name: Noveen

The

Owner:

Age: 14 years, 3 weeks, 4 days

Born: April 5th, 2010

Adopted: 13 years, 10 months ago

Adopted: June 30th, 2010

Statistics

- Level: 1

- Strength: 17

- Defense: 10

- Speed: 10

- Health: 10

- HP: 10/10

- Intelligence: 0

- Books Read: 0

- Food Eaten: 0

- Job: Store Clerk

Chapter 18 - Noveen

"The cypress and redwood in this place would have been worth a fortune if somebody had come up and got it before it went to hell," Jack said. He bent down, seized the end of a protruding board, and pulled. It came up, bent almost like taffy, then broke off - not with a snap but a listless crump. A few woodlice came strolling from the rectangular hole below it. The smell that puffed up was dank and dark.

"No scavenge, no salvage, and nobody up here partying hearty," Wireman said. "No discared condoms or step-ins, not a single JOE LOVES DEBBIE spray-painted on a wall. I don't think anyone's been up here since John chained the door and drove away for the last time. I know that's hard to believe-"

"No," I said, "It's not. The Heron's Roost at this end of the Key has belonged to Perse since 1927. John knew it, and made sure to keep it that way when he wrote his will. Elizabeth did the same. But it's not a shrine." I looked into the room opposite the formal parlor. It might once have been a study. An old rolltop desk sat in a puddle of stinking water. There were bookshelves, but they stood empty. "It's a tomb."

"So where do we look for these drawings?" Jack asked.

"I have no idea," I said. "I don't even . . . " A chunk of plaster lay in the doorway, and I kicked it. I wanted to send it flying, but it was too old and wet; it only disintegrated. "I don't even think there are any more drawings. Not now that I see the place."

I glanced around again, smelling the wet reek."You could be right, but I don't trust you," Wireman said. "Because, muchacho, you're in mourning. And that makes a man tired. You're listening to the voice of experience."

Jack went into the study, squishing across damp boards to get to the old rolltop. A drop of water plinked down on the visor of his cap, and he looked up. "Ceiling's caving in," he said. "There was probably at least one bathroom overhead, maybe two, and maybe a roof cistern to catch rainwater, back in the day. I can see a hanging pipe. One of these years it's gonna come all the way down, and this desk will go bye-bye."

"Just make sure you don't go bye-bye, Jack," Wireman said."It's the floor I'm worried about right now," he said. "Feels mushy as hell.""Come back, then," I said."In a minute. Let me check this, first."

He ran the drawers, one after the other. "Nothing," he said. "Nothing . . . more nothing . . . " He paused. "Here's something. A note. Handwritten."

"Let's see it," Wireman said.

Jack brought it to him, taking big, careful steps until he got past the wet part of the floor. I read over Wireman's shoulder. The note was scrawled on plain white paper in a big flat man's hand:

Wireman touched Table X 2 and said, "The table is leaking. Does the rest of this mean anything to you Edgar?"

It did, but for a moment my damned sick memory refused to give it up. I can do this, I thought . . . and then thought sideways. First to Ilse saying Share your pool, mister?, and that hurt, but I let it because that was the way in. What followed was the memory of another girl dressed for another pool. This girl was all breasts and long legs in a black tank suit, she was Mary Ire and Hockney had painted her - Gidget in Tampa, she had called her younger self - and then I had it. I let out a breath I hadn't known I was holding.

"DD was Dave Davis," I said. "In the Roaring Twenties he was a Suncoast mogul.""How do you know that?"

"Mary Ire told me," I said, and a cold part of me that would probably never warm up again could appreciate the irony; life is a wheel, and if you wait long enough, it always comes back around to where it started. "Davis was friends with John Eastlake, and apparently supplied Eastlake with plenty of good liquor."

"Champers," Jack said. "That's champagne, right?"Wireman said, "Good for you, Jack, but I want to know what Table is. And cera.""It's spanish," Jack said. "You should know that."

Wireman cocked an eyebrow at him. "You're thinking of ser� - with an s. As in que ser�, ser�."

"Doris Day, 1956," I said. "The future's not ours to see." And a good thing, too, I thought. "One thing I'm pretty sure of it that Davis was right when he said this was the last delivery." I tapped the date: August 19th. "The guy sailed for Europe in October 1926 and never came back. He disappeared at sea - or so Mary Ire told me."

"And cera?" Wireman asked."Let it go for now," I said. "But its strange - Just this one piece of paper."

"A little odd maybe, but not completely strange," Wireman said. "If you were a widower with young daughters, would you want to take your bootlegger's last receipt with you to your new life?"

I considered it, and decided he had a point. "No . . . but I'd probably destroy it, along with my stash of French postcards."

Wireman shrugged. "We'll never know how much incriminating paperwork he did destroy . . . or how little. Except for having a little drinkie now and then with his pals, his hands may have been relatively clean. But, muchacho . . . " He put a hand on my shoulder. "The paper is real. We do have it.And if something's out to get us, maybe something else is looking out for us . . . just a little. Isn't that possible?"

"It would be nice to think so, anyway. Let's see if there's anything else."

It seemed at first there wasn't. We poked around all the downstairs rooms and found nothing but near-disaster when my foot plunged through the flooring in what must once have been the dining room. Wireman and Jack were quick, however, and as least it was my bad leg that went down; I had my good one to brace myself with.

There was no hope of checking above gound-level. The staircase went all the way up, but beyond the landing and a single ragged length of rail beside it, there was only blue sky and the waving fronds of one tall cabbage plant. The second floor was a remnant, the third complete toast. We started back toward the kitchen and out makeshift step-down to the outside world with nothing to show for our exploration but an ancient note announcing a booze delievery. I have an idea what cera might mean, but without knowing where Perse was, the idea was useless.

And she was here.She was close.Why else make it so fucking hard to get here?

Wireman was in the lead, and he stopped so suddenly I ran into him. Jack ran into me, whacking me in the butt with the picnic basket.

"We need to check the stairs," Wireman said. He spoke in the tone of a man who can't believe he has been such a dump cluck.

"I beg pardon?" I asked."We need to check the stairs for a ha-ha. I should have thought of that first thing. I must be losing it."

"What's a ha-ha?" I asked.

Wireman was turning back. "The one at El Palacio is four steps up from the bottom of the main staircase. The idea - she said it was her father's - was to have it close to the front in case of fire. There's a lockbox inside it, and nothing much inside the lockbox now but a few old souvenirs and some pictures, but once she kept her will and her best pieces of jewelry in there. Then she told her lawyer. Big mistake. He insisted she move all that stuff to a safe deposit box in Sarasota."

We were at the foot of the stairs now, back near the hill of dead wasps. The stink of the house was think around us. He turned to me, his eyes gleaming. "Muchacho, she also kept a few very valuable china figures in that box." He surveyed the wreck of the staircase, leading up to nothing but senseless shattery and blue sky beyond. "You don't suppose . . . if Perse is something like a china figure that John fished off the bottom of the Gulf . . . you don't suppose she's hidden right here, in the stairs?"

"I think anything's possible. Be careful. Very.""I'll bet you anything that there's a ha-ha," he said. "We repeat what we learn as children."

He brushed away the dead wasps with his boot - they made a whispery, papery sound - and then knelt at the foot of the stairs. He examined the first stair riser, then the second, then the third. When he got to the fouth, he said: "Jack, give me the flashlight."

It was easy to tell myself that Perse wasn't hiding in a secret compartment under the stairs - that would be too easy - but I remembered the chinas Elizabeth liked to secrete in her Sweet Owen cookie-tin and felt my pulse speed up as Jack rummaged in the picnic basket and brought out the monster flashlight with the stainless steel barrel. He slapped it into Wireman's hand like a nurse handing a doctor an instrument at the operating table.

When Wireman trained the light on the stair, I saw the minute gleam of gold: tiny hinges set at the far end of the tread. "Okay," he said, and handed back the flashlight. "Put the deam on the edge of the tread."

Jack did as told. Wireman reached for the lip of a riser, which was meant to swing up on those tiny hinges.

"Wireman, just a minute," I said.He turned to me."Sniff it first," I said."Say what?""Sniff it. Tell me if it smells wet."

He sniffed the stair with the hinges at the back, then turned to me again. "A little damp, maybe, but everything in here smells that way. Want to be a little more specific?"

"Just open it very slowly, okay? Jack, shine the light directly inside. Look for wetness, both of you."

"Why, Edgar?" Jack asked.

"Because the Table is leaking, she said so. If you see a ceramic container - a bottle, a jug, a keg - that's her. It'll almost certainly be cracked, and maybe broken wide open."

Wireman pulled in a breath, then let it out. "Okay. As the mathematician said when he divided by zeo, here goes nothing."

He tried to lift the stair, with no result.

"It's locked. I see a tiny slot . . . must have been a hell of a small key - ""I've got a Swiss Army knife," Jack offered.

"Just a minute," Wireman said, and I saw his lips tighten down as he applied upward pressure with his fingertips. A vein stood out in the hollow of his temple.

"Wireman," I started, "be carefu-"

Before I could finish, the lock - old and tiny and undoubtedly rotted with rust - snapped. The stair-tread flew up and tore off the hinges. Wireman tumbled backward. Jack caught him, and then I caught Jack in a clumsy one-armed hug. The big flashlight hit the floor but didn't break; its big beam rolled spotlighting that grisly pile of dead wasps.

"Holy shit," Wireman said, regaining his feet. "Larry, Curly, and Moe."

Jack picked up the flashlight and shone it into the hole in the stairs. "What?" I asked. "Anything? Nothing? Talk!"

"Something, but its not a ceramic bottle," he said. "It's a metal box. Looks like a candy box, only bigger." He bent down.

"Maybe you better not," Wireman said.

But it was too late for that. Jack reached in all the way up to his elbow, and for one moment I was sure his face would lengthen in a scream as something battened on his arm and yanked him down to the shoulder. Then he sraighted again. In his hand he held a heart-shaped tin box. He held it out to us. On the top, barely visible beneath speckles of rust, was a pink-cheeked angel. Below that, in old-fashioned script, these painted words:

ELIZABETHHER THINGS

Jack looked at us questioningly.

"Go on," I said. It wasn't Perse - I was positive of that now. I left both disappointed and relieved. "You found it; go on and open it."

"It's the drawings," Wireman said. "It must be."

I thought so, too. But it wasn't. What Jack lifted out of the rusty old heart-shaped box was Libbet's dolly, and seeing Noveen was like coming home.

Ouuuu, her black eyes and scarlet smiling mouth seemed to be saying. Ouuu I been in here all that time, you nasty man.

When I saw her come out of that box like a disinterred corpse out of a crypt, I felt a terrible helpless horror come stealing through me, beginning at the heart and radiating outward, threatening to first loosen all my muscles and then unknit them completely.

"Edgar?" Wireman asked sharply. "All right?"

I did my best to get hold of myself. Mostly it was the thing's toothless smile. Like the jockey's cap, that smile was red. And as with the jockey's cap, I felt that if I looked at it too long, it would drive me mad. That smile seemed to insist that everything which had happened in my new life was a dream I was having in some hospital ICU while machines kept my twisted body alive a little longer . . . and maybe that was good, for the best, because it meant nothing had happened to Ilse.

"Edgar?" When Jack stepped toward me, the doll in his hand bobbed in its own grotesque parody of concern. "You're not going to faint, are you?"

"No," I said. "Let me see that." And when he tried to pass it to me: "I don't want to take it. Just hold it up."

He did as I asked, and I understood at once why I'd had that feeling of instant recognition, that sense of coming home. Not because of Reba or her more recent companion - although all three were ragdolls, there was that similarity. No, it was because I had seen her before, in several of Elizabeth's drawings. As first I'd assumed she was Nan Melda. That was wrong, but -

"Nan Melda gave this to her," I said.

Sure, Wireman agreed. "And it must have been her favorite, because it was the only one she ever drew. The question is, why did she leave it behind when the family left Heron's Roost? Why did she lock it away?"

"Sometimes dolls fall out of favor," I said. I was looking at that red and smiling mouth. Still red after all these years. Red like the place memories went to hide when you were wounded and couldn't think sraight. "Sometimes dolls get scary."

"Her pictures talked to you, Edgar," Wireman said. He waggled the doll, then handed it back to Jack. "What about her? Will the doll tell you what we want to know?"

"Noveen," I said. "Her name's Noveen. And I wish I could say yes, but only Elizabeth's pencils and pictures speak to me."

"How do you know?"A good question. How did I know?

"I just do. I bet she could have talked to you, Wireman. Before I fixed you. When you still had that little twinkle."

"Too late now," Wireman said. He rummaged in the food-stash, found the cucumber strips, and ate a couple. "So what do we do? Go back? Because I have an idea that if we go back, 'chacho, we'll never summon the testicular fortitude to return."

I thought he was right. And meanwhile, the afternoon was passing all around us.

Jack was sitting on the stairs, his butt on a riser two or three above the ha-ha. He was holding the doll on his knee. Sunshine fell through the shattered top of the house and dusted them with light. There were strangely evocative, would have made a terrific painting: Young Man and Doll. The way he was holding Noveen reminded me of something, but I couldn't put my finger on just what. Noveen's black shoebutton eyes seemed to look at me, almost smugly. I seen a lot, you nasty man. I seen it all, I know it all. Too bad I'm not a picture you can touch with your phantom hand, aint it?

Yes it was."There was a time when I could have made her talk," Jack said.

Wireman looked puzzled, but I felt that little click you get when a connection you've been trying to make finally goes through. Now I knew why the way he was holding the doll looked so familiar.

"Into ventriloquism, were you?" I hoped I sounded casual, but my heart was starting to bump against my ribs again. I had an idea that here at the south end of Duma Key, many things were possible. Even in broad daylight.

"Yeah," Jack said with a smile that was half-embarassed, half-reminiscent. "I bought a book about it when I was only eight, and stuck with it mostly because my Dad said it was like throwing money away, I gave up on everything." He shrugged, and Noveen bobbed a bit on his leg. As is she were also trying to shrug. "I never got great at it, but I got good enough to win the sixth-grade Talent Competition. My Dad hung the medal on his office wall. That meant a lot to me."

"Yeah," Wireman said. "There's nothing like an atta-boy from a doubtful dad."

Jack smiled, and as always, it illuminated his whole face. He shifted a little, and Noveen shifted with him. "Best thing, though? I was a shy kid, and ventriloquism broke me out a little. It got easier to talk to people - I'd sort of pretend I was Morton. My dummy, you know. Morton was a wiseass who'd say anything to anybody."

"They all are," I said. "It's a rule, I think."

Then I got into junior high, and ventriloquism started to seem like a nerd talent compared to skateboarding, so I gave it up. I don't know what happened to the book. Throw Your Voice it was called."

We were silent. The house breathed dankly around us. A little while ago, Wireman had killed a charging alligator. I could hardly believe that now, even though my ears were still ringing from the gunshots.

Then Wireman said: "I want to hear you do it. Make her say, 'Buenos dias, amigos, mi nombre es Noveen, and la mesa is leaking."

Jack laughed. "Yeah, right.""No - I'm serious.""I can't. If you don't do it for awhile, you forget how."

And from my own research, I knew he could be right. In the matter of learned skills, memory comes to a fork in the road. Down one branch are the it's-like-riding-a-bicycle skills; things which, once learned are almost never forgotten. But the creative, ever changing forebrain skills have to be practiced almost daily, and they are easily damaged or destroyed. Jack was saying ventriloquism was like that. And while I had no reason to doubt him - it involved creating a new personality, after all, as well as throwing once's voice - I said: "Give it a try."

"What?" He looked as me. Smiling. Puzzled."Go on, take a shot.""I told you, I can't - ""Try anyway."

"Edgar, I have no idea what she would sound like even if I could still throw my voice.""Yeah, but you've got her on your knee, and it's just us chickens, so go ahead.""Well shit." He blew hair off his forehead. "What do you want her to say?"Wireman said, very quietly indeed: "Why don't we just see what comes out?"

Jack sat with Noveen on his knee for a moment longer, their heads in the sun, little bits of disturbed dust from the stairs and the ancient hall carpet floating around their faces. Then he shifted his grip so that his fingers were on the doll's rudiment of a neck and her cloth shoulders. Her head came up.

"Hello boys," Jack said, only he was trying not to move his lips and it came out Hello, oys.

He shook his head; the disturbed dust flew. "Wait a minute," he said. "That sucks."

"Got all the time in the world," I told him. I think I sounded calm, but my heart was thudding harder than ever. Part of what I was feeling was fear for Jack. If this worked, it might be dangerous for him.

He stretched out his throat and used his free hand to massage his Adam's apple. He looked like a tenor getting ready to sing. Or like a bird, I thought. A Gospel Hummingbird, maybe. Then he said, "Hello, boys." It was better, but -

"No," he said. "Shit-on-toast. Sounds like that old blond chick. Mae West. Wait."

He massaged his throat again. He was looking up into hte cascading bright as he did it, and I'm not sure he knew that his other hand - the one on the doll - was moving. Noveen looked first at me, then at Wireman, then back at me. Black shoebutton eyes. Black beribboned hair cascading around a chocolate-cookie face. Red O of a mouth. An Ouuu, you nasty man mouth if there ever was one.

Wireman's hand gripped mine. It was cold.

"Hello, boys," Noveen said, and although Jack's Adam's apple bobbed up and down, his lips barely moved on the b at all.

"Hey! How was that?""Good." Wireman said, sounding as calm as I didn't feel. "Have her say something else.""I get paid extra for this, don't I boss?""Sure," I said. "Time and a ha-"

"Ain't you gone draw nuthin?" Noveen asked, looking at me with those round black eyes. They really were shoebuttons, I was almost sure of it.

"I have nothing to draw," I said. "Noveen."

"I tell you sumpin you c'n draw. Whereat ya pad?" Jack was now looking off to the side into the shadows leading to the ruined parlor, bemused, eyes distant. He looked neither conscious or unconsious; he looked someplace between.

Wireman let go of me and reached into the food-bag, where I had stowed the two Artisan pads. He handed me one. Jack's fand flexed a bit, and Noveen appeared to bend her head slightly to study it as I first flipped back the cover then unzipped the pouch that help me pencils. I took one.

"Naw, naw. Use one of hers."

I rummaged again, and took out Libbit's pale green. It was the only one still long enough to afford a decent grip. It must have not been her favorite color. Or maybe it was just that Duma's greens were darker.

"All right, now what?""Draw me in the kitchen. Put me up agin the breadbox, that do fine.""On the counter, do you mean?""Think I was talkin about the flo?"

"Christ," Wireman muttered. The voice had been changing steadily with each exchange; now it wasn't Jack's at all. And whose was it, given the fact that in its prime the only ventriloquism available to make the doll speak had been provided by a little girl's imagination? I thought it had been Nan Melda's then, and that we were listening to a version of that voice now.

As soon as I began to work, the itch swept down my missing arm, defining it, making it there. I sketched her sitting against an old-fashioned breadbox, then few her legs dangling over the edge of the counter. With no pause or hesitation - something deep inside me, where the pictures came from, said to hesitate would be to break the spell while it was still forming, while it was still fragile - I went on and drew the little girl next to the counter. Standing beside the counter and looking up. Little four-year old-girl in a pinafore. I could not have told you what a pinafore was before I drew one over little Libbit's dress as she stood there in the kitchen beside her doll, as she stood there looking up, as she stood there -

Shhhhh--with one finger to her lips.

Now moving quicker than ever, the pencil racing, I added Nan Melda, seeing her for the first time outside that photograph where she was holding the red picnic basket bunched in her arms. Nan Melda bent over the little girl, her face set and angry.

No, not angry-

Scared.That's what Nan Melda is, scared near to death. She knows something is going on, Libbit knows something is going on, and the twin's know, too - Tessie and Lo-Lo are as scared as she is. Even that fool Shannington knows something's wrong. That's why he's taken to staying away as much as he can, preferring to work on the farm shoreside instead od coming out to the Key.

And the Mister? When he's been here, the Mister's too mad about Adie, who's run off to Atlanta, to see what't right in front of his eyes.

At first Nan Melda thought what was in front of her eyes was just her own imagination, picking up on the babby-uns' games; surely she never really saw no pelicans or herons flying upside-down, or the hosses smiling at her when Shannington brought over the two-team from Nokomis to give the girls a ride. And she guessed she knew why the little ones were scairt of Charley; there might be mysteries on Duma now, but that ain't one of em. That was her own fault, although she meant well -

"Charley!" I said. "His name's Charley!"Noveen cawed her laughing assent.

I took the other pad out of the food-sack - almost ripped it out - and threw back the cover so savagely that I tore it half off. I groped among the pencils and found the stub of Libbit's black. I wanted black for this side-drawing, and there was just enough to pinch between my thumb and finger.

"Edgar," Wireman said. "For a minute there I thought I saw . . . it looked like-""Shut up!" Noveen cried. "Ne'mine no mojo arm! You gone want to see this, I bet."

I drew quickly, and the jockey came out of the white like a figure out of heavy fog. It was quick, the strokes careless and hurried, but the essence was there: the knowing eyes and the broad lips that might have been grinning with either mirth or malevelence. I had no time to color the shirt and the breeches, but I fumbled for the pencil stamped Plain Red (one of mine) along its barrel and added the awful cap, scribbling it in. And once the cap was there you knew that the grin really was: a nightmare.

"Show me!" Noveen cried. "I want to see if y'got it right!"I held the picture up to the doll, who now sat straight on Jack's leg while Jack slumped against the wall beside the saircase, looking off into the parlor.

"Yep," Noveen said. "That's tge bugger who scared Melda's girls. Mos' certainly.""What-?" Wireman began, and shook his head. "I'm lost."

"Melda seen the frog too," Noveen said. "The one the babbies call the big boy. The one wit d'teef. That's when Melda finally corner Libbit in d'kitchen. To make her talk."

"At first Melda thought the stuff about Charley was just little kids scaring each other, didn't she?"

Noveen cawed again, but her shoebutton eyes stared with what could have been horror. Of course, eyes like that can look like anything you wan them to, can't they? "That's right, sugar. But when she seen ole Big Boy down there at the foot of the lawn, crossin the driveway and goin into the trees . . . "

Jack's hand flexed. Noveen's head shook slowly back and forth, indicating the collapse of Nan Melda's defences.

I shuffled the pad with Charley the jockey on it to the bottom and went back to the picture of the kitchen: Nan Melda looking down, the little girl looking up with her finger on her lips - Shhhh!- and the doll bearing silent witnessfrom her place against the breadbox. "Do you see it?" I asked Wireman. "Do you understand?""Sort of . . . ""Sugar-candy was mos'ly done, once she was out," Noveen said. "Thass what it came down to."

"Maybe at first, Melda thought Shannington was moving the lawn jockey around as kind of a joke - because he knew the three girls were scared of it."

"Why in God's name would they be?" Wireman asked.

Noveen said nothing, so I passed my missing hand over the Noveen in my drawing - the Noveen leaning against the breadbox - and then the one on Jack's knee spoke up. As I sort of knew she would.

"Nanny din' mean nothin bad. She knew they 'us scairt of Charley- this 'us befo the bad things started - an so she tole em in a bedtime story to try an make it better. Made it worse instead, as sometimes happens with small chirrun. Then the bad woman came - the bad white woman from the sea - n dat bitch made it worse still. She made Libbit draw Charley alive, for a joke. She had other jokes, too."

I threw back the sheet with Libbit going Shhhh, seized my Burnt Umber from my pack - now it didn't seem to matter whose pencils I used - and sketched the kitchen again. Here was the table, with Noveen lying on her side, one arm cast up over her head, as if in supplication. Here was Libbit, now wearing a sundress and an of dismay achieved in no more than half a dozen racing lines. And here was Nan Melda, backing away from the open breadbox and screaming, because inside -

"Is that a rat?" Wireman asked.

"Big ole blind woodchuck," Noveen said. "Same thing as Charley, really. She got Libbit to draw it in the breadbox, and it was in the breadbox. A joke. Libbit 'us sorry, but the bad water-woman? Nuh-uh. She never sorry."

"And Elizabeth - Libbit - had to draw," I said. "Didn't she?""You know dat," Noveen said. "Don't you?"I did. Because the gift is hungry.

Once upon a time, a little girl fell and did her head wrong in just the right way. And that allowed something - something female - to reach out and make contact with her. The amazing drawings that followed had been the come-on, the carrot dangling at the end of the stick. There had been smiling horses and troops of rainbox-colored frogs. But once Perse was out - what had Noveen said? - sugar-candy was mos'ly done. Libbit Eastlake's talent had turned in her hand like a knife. Except it was no longer really her hand. Her father didn't know. Adie was gone. Maria and Hannah were away at Braden School. The twins couldn't understand. But Nan Melda because to suspect and . . .

I flipped back and looked at the little girl with the finger to her lips. She's listening, so shhh. If you talk, she'll hear, so shhh. Bad things can happen, and worse things are waiting. Terrible things in the Gulf, waiting to drown you and take you to a ship where you'll live something that's not a life. And if I try to tell? Then the bad things may happen to all of us, and all at once.

Wireman was perfectly still beside me. Only his eyes moved, sometimes looking at Noveen, sometimes looking at the pallid arm that flickered in and out of view on the right side of my body.

"But there was a safe place, wasn't there?" I asked. "A place where she could talk. Where?""You know," Noveen said."No, I - ""Yessir, you do. You sho do. You only forgot awhile. Draw it and you see."

Yes, she was right. Drawing was how I'd re-invented myself. In that way, Libbit(where our sister)was my kin. For both of us, drawing was how we remembered how to remember.

I flipped to a clean sheet. "Do I have to use one of her pencils?" I asked.

"Not no mo. you be fine with any."

So I rummaged in my pack, found my Indigo, and began drawing. I drew the Eastlake swimming pool with no hesitation - it was like giving up thought and allowing muscle memory to punch in a phone number. I drew it as it had been when it had been bright and new and full or clean water. The pool, where for some reason Perse's hold slipped and her hearing failed.

I drew Nan Melda, up to her shins, and Libbit up to her waist, with Noveen tucked under her arm and her pinafore floating around her.

Words floated out of the strokes.

Where ya new doll now? The china doll?In my special treasure-box. My heart-box.So it had been there, at least for a while.And what her name?Her name is Perse.Percy a boy's name.And Libbit, firm and sure: I can't help it. Her name is Perse.All right den. And you say she can't hear us here.I don't think so . . . That's good. You say you c'an make things come. But listen to me, child-

"Oh my God," I said. "It wasn't Elizabeth's idea. It was never Elizabeth's idea. We should have known."

I looked up from the picture I had drawn of Nan Melda and Libbit standing in the pool. I realized, in a distant way, that I was very hungry.

"What are you talking about, Edgar?" Wireman asked.

"Getting rid of Perse was Nan Melda's idea." I turned to Noveen, still sitting on Jack's knee. "I'm right, aren't I?"

Noveen said nothing, so I passed my right hand over the figures in my swimming-pool drawing. For a moment I saw that a hand, long fingernails and all.

"Nanny didn't know no better," Noveen said in an instant later from Jack's leg. "And Libbit be trustin Nanny."

"Of course she did," Wireman said. "Melda was almost the child's mother."

I had visualized the drawing and erasing as happenings in Elizabeth's room, but now I knew better. It had happened at the pool. Perhaps even in the pool. Because the pool had been, for some reason, safe. Or so little Libbit had believed.

Noveen said, "It din' make Perse gone, but it sholy did get her attention. I think it hoit dat bitch." The voice sounded tired now, croaky, and I could see Jack's Adam's apple sliding up and down in his throat again. "I hope it did!"

"Yes," I said. "Probably it did. So . . . what came next?" But I knew. Not the details, but I knew. The logic was grim and irrefutable. "Perse took her revenge on the twins. And Elizabeth and Nan Melda knew. They knew what they did. Nan Melda knew what she did."

"She knew," Noveen said. It was still a female voice, but it was edging closer to Jack's all the time. Whatever the spell was, it wouldn't hold for much longer. "She held on until the Mister found their tracks down on Shade Beach - tracks goin into the water - but after that she couldn't hold on no longer. She felt she got her babby-uns killed."

"Did she see the ship?" I asked.

"Seen it that night. You cain't see that boat at night and not believe." I thought of my Girl and Ship paintings and knew that was the truth.

"But even before the Mister rung the high sheriff on the s'change to say his twins was missin and probably drownded, Perse done spoke to Libbit. Tole her how it was. An' Libbit tole Nanny."

The doll slumped, its round cookie-face seeming to study the heart-shaped box from which it had been exhumed.

"Told her what, Noveen?" Wireman asked. "I don't understand."

Noveen said nothing. Jack, I thought, looked exhausted even though he hadn't moved at all.

I answered for Noveen. "Perse said, 'Try to get rid of me again and the twins are just the beginning. Try again and I'll take your whole family, one by one, and save you for last.' Isn't that right?"

Jack's fingers flexed. Noveen's rag head nodded slowly up and down.

WIreman licked his lips. "That doll," he said. "Exactly whose ghost is it?"

"There are no ghosts here, Wireman." I said.Jack moaned."I dont know what he's been doing, amigo but he's done," Wireman said.

"Yes, but we're not." I reached for the doll - the one that had gone everywhere with the child artist. And as I did, Noveen spoke to me for the last time, in a voice that was half hers and half Jack's, as if both of them were struggling to come through at the same time.

"Nuh-uh, not dat hand - you need day hand to draw with'."

And so I reached out the arm I used to lift Monica Goldstein's dying dog out of the street six months ago, in another life and universe. I used that hand to grasp Elizabeth's doll and lift it off Jack's knee.

"Edgar?" Jack said, straightening up. "Edgar, how in hell did you get your-"

-arm back, I suppose he said, but I don't know for sure; I didn't hear the finish. What I saw where those black eyes and that black maw of a mouth ringed with Red. Noveen. All these years she had been down there in the double dark - under the stair and in the tin box - waiting to spill her secrets, and her lipstick had stayed fresh all the while.

Are you set? she whispered inside my head, and that voice wasn't Noveen's, wasn't Nan Melda's (I was sure of that), wasn't even Elizabeth's; that was all Reba. You all set and ready to draw, you nasty man? Are you ready to see the rest? Are you ready to see it all?

I wasn't . . . but I would have to be.

For Ilse.

"Show me your pictures," I whispered, and that red mouth swallowed me whole.

Credits

Profile by ![]() Integrity

Integrity

Profile Art by ![]() NikonD40

NikonD40

Special thanks to User not found: c0c0nut for

helping to tweak the coding

Story is an excerpt from Stephen King's Duma Key

Art

By

By ![]() NikonD40

NikonD40

By ![]() NikonD40

NikonD40

By ![]() NikonD40

NikonD40

By ![]() NikonD40

NikonD40

By User not found: akimichi

By ![]() Aeiou

Aeiou

Pet Treasure

Sewcreepy Plushie

Pinhart

Voodoo Plushie

Nightmare Feli Voodoo Plushie

Bunny Voodoo Doll

Dyed Red Rreign Voodoo Doll

Bleached Red Rreign Voodoo Doll

Blue Silly Masquerade Voodoo Doll

Pumpkin Voodoo Doll Plushie

Ghostly Voodoo Plushie

Undead Porcine Gentleman Plushie

Bottled Voodoo Doll

Love Voodoo Plushie

Cursed Voodoo Doll

Keiths Cursed Voodoo Doll

Green Voodoo Doll

Pink Voodoo Doll

Graveyard Voodoo Doll

Blue Voodoo Doll

Darkmatter Voodoo Doll

Arid Voodoo Doll

Sun Voodoo Doll

Twilight Voodoo Doll

Bloodred Voodoo Doll

Tigrean Voodoo Plushie

Voodoo Bovyne Plushie

Voodoo Montre Plushie